Recently while burrowing around the rabbit hole of TarotTube, I noted a series of videos, mostly deck reviews, where “diversity and inclusion” are mentioned on a regular basis. This is to be expected, I suppose, given modern Western culture and that this marginalized spiritual practice has been adopted by practitioners who often belong to marginalized groups. A couple of the videos, however, did catch my attention with what I perceived to be an unnecessarily threatening tone with regard to the artistic and capitalistic mechanisms by which tarots are produced. To clarify, the YouTubers suggested that tarots which did not attempt to represent the whole of humanity should be “boycotted” to a degree. Mention, too, was made of not supporting tarot kickstarters where the breadth of the species was not artistically celebrated in some way. This position poses a host of problems for me as I fancy myself a proponent of rationality and individual liberties.

Oftentimes people who take these kinds of rather militant-sounding stances are quite intolerant of what they perceive as intolerance in others. In many cases, these feelings are justified, and eventually rules against actual discrimination, as opposed to perceived discrimination, become the law of the land. Ask anyone who has ever paid a ticket for parking in a space reserved as wheelchair accessible. Generally, these rules are meant to further civilize the public sphere, where social and “official” communication and interaction take place. However, the law cannot legislate thought, those burning emotions and notions that chafe even unwillingly against the bridle of social pressure. To wit, we can make illegal any action that seems discriminatory, but we cannot make illegal the thoughts and beliefs which generate those discriminatory actions.

Unfortunately, over the years, I have heard many arguments put forward like those of the YouTubers, but I sometimes find their rationales hard to follow. One of the most oft-beaten drums has to do with the past. Someone will say, “Don’t let history be the excuse,” meaning that historical discrimination cannot be allowed a pass. To an extent, I can fully agree, but where their logic seems to falter is in the recognition of simple fact: historical and social contexts do matter in the way we perceive artifacts of the past. The tarot, like any other historical artifact, is a product of its time and the people who lived there and then. And especially when the subject is representation in the tarot, I would also submit that being ignored or neglected is not the same as being actually abused. One example in particular involves the founding deck of U.S. Games Systems, the 1JJ Swiss Tarot. The deck was originally produced in Switzerland in the 1830s, and some commentators within the last few years have stated that the deck is racist because the only black figure in the deck is the Devil. I proffer that this is untrue.

The Devil is the only dark figure in the deck because of the ancient symbolic nature of light versus dark, white versus black as colors, not as races. Historically, one might note the Roman candidati, candidates for the Senate who wore exquisitely white robes to indicate their pure character and intentions. The fifteenth trump of the 1JJ Swiss is dark because he is the Devil; he is not the Devil because he is of African descent. In fact, given the rather high artistic quality of the deck itself, I propose that the exaggerated facial features of the Devil in the 1JJ Swiss exhibit a more anti-Semitic than anti-African stance. The deck also replaces the Popesse and the Pope with the gods Juno and Jupiter respectively. This was what we might now call a “political move” done to placate both the 19th-century Swiss Catholics who did not want their sacred emblems on vulgar playing cards and the ardent Swiss protestants who did not want their vulgar playing cards infiltrated with Papist propaganda.

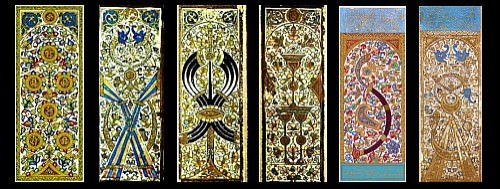

But what of racial diversity? I suspect that for Switzerland of the 1830s, the deck is as diverse as the population that produced it. As for its possibly anti-Semitic undertones, I will come back to that. With regard to racial or ethnic diversity in historical European decks, don’t look for it. And furthermore, don’t be offended by its absence. Historical card makers throughout the centuries are not looking to placate racial or any other marginalized groups. While the images that appear on the tarot’s fifth trump suit can likely be ascribed to Catholic Renaissance symbolism, their codification over the years probably has as much to do with the capitalist motivations of their makers as any edifying symbolic language. And their target audiences were not particularly diverse.

After the mid-1600s and the decrees of the French Sun King Louis XIV that created the Code Noir (Black Code), I doubt there were very many people of African descent trying to get into the heart of France or any of that country’s colonies by choice. Even though the port and trade city of Marseille—after which one of the most widely used tarots is named—was bustling and metropolitan, I suspect that the native French paid little attention to travelling African traders except for commerce and barter. In addition to being Black, being non-Christian was also a social obstacle.

In many European countries, being Jewish was practically if not actually illegal, and if a person decided to maintain a Jewish identity, he or she would be openly discriminated against. The Jewish populations would be shunned, forced out of employment, forced to convert, or worse. Our word “ghetto” comes to us unchanged from the Italian word for the Venetian island where the 16th-century Italian Jews were forced to live. Some of these attitudes—mind-boggling as they are—can still be found today. But tarot card manufacturers weren’t catering to that market. And because of the public and social abuse that these groups suffered, I am glad that the tarot producers did not engage what would most certainly have been inflammatory depictions. I repeat, I am very glad that tarot did not try to display images of “under-represented” peoples because those images would have been far worse actively than their passive absence.

And what of the Moors, the word that Shakespeare used to describe the protagonist of Othello? The racial mix of the heterogeneous Moors may have included everyone from the Iberian Spanish down to Sub-Saharan Africa, but they do share a religion: Islam. Many scholars posit that playing cards—and later the tarot—are ultimately derived from the Turkish Mamluk decks, a product of a predominantly Muslim culture. The Moors liked playing cards, so where do we find the Muslim tarots of the 16th and 17th centuries? Well, we don’t because the Muslims of the time–and even to this day–have socio-religious prohibitions against the artistic representation of the human form, what they call “idolatry.” So you see why the European card makers weren’t seeking that market either.

Over the centuries, the tarot stayed essentially a game and method of divination for mainland Europe. The world did not begin to shrink until the 19th and 20th centuries as transportation and communication technologies brought and continue to bring us closer than ever. With that communication and travel, with the development of social and psychological sciences, and with the progress of the physical and technological sciences, certain cultures and countries have made great strides in the areas of human rights over the last two centuries, whether people want to believe it or not.

Yes, the process has been slow, and yes, the process is not over, but it is moving forward. Even as late as the American tarot renaissance of the late 1960s and 1970s, the most melanated word to be found in most books on the subject was the ever-dependable “swarthy.” Many have argued that representational integration within the tarot has also been too slow whether we are discussing the appearance of same-sex couples, of different races, of different gender identities, or of different body types.

There have been more and more attempts over the years, and certainly they try, lauding themselves for bringing representation to the fore. Some succeed, some do not. Inclusivity that does nothing but highlight tokenism would be best avoided, in my opinion. The Morgan-Greer Tarot of the mid-seventies features a Black woman on the nine of pentacles. In the thirty-five years that I have worked with this deck, she simply is. She is not an afterthought; she is not a representative of an underserved minority. She is the essence of distinguished comfort and ease. In this case, the Morgan-Greer images are created in yet a different time. They are the product of the aforementioned American tarot renaissance, and the head and heart of the deck is deeply rooted in young-Boomer, post-Hippie openness bathed with an artistic facility that continues to make the deck a best seller fifty years later.

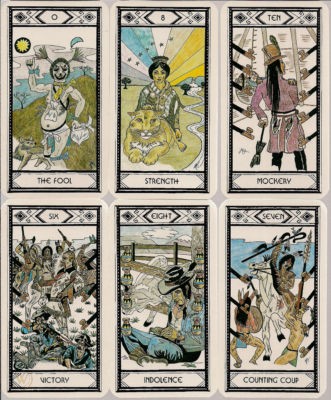

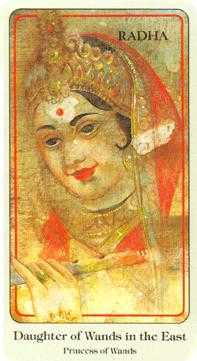

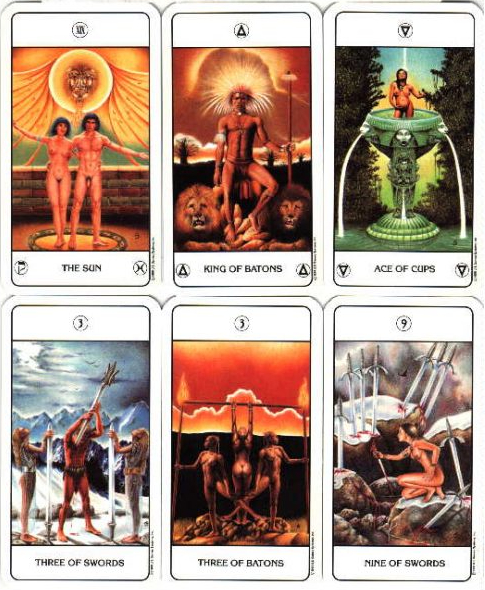

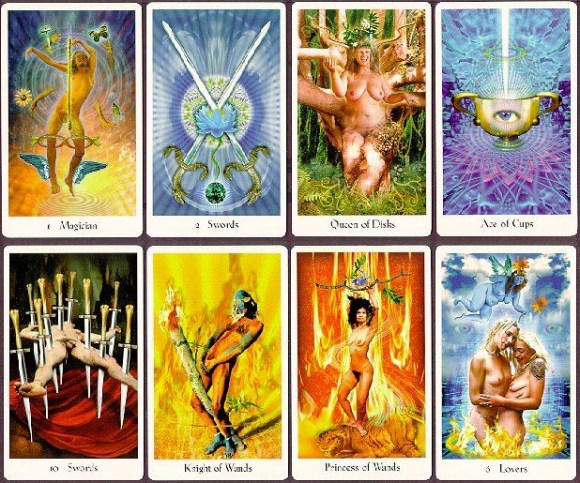

Representation took another upshot in the late eighties and nineties, and again, the results were mixed in my opinion. The Native American Tarot, released in 1982 by U.S. Games Systems, was one of the two decks my uncle owned; he enjoyed it, but the deck never resonated with me. I find the artwork lacking and the theme a bit condescending, as is always the danger with attempts at thematic diversity of any kind. As the nineties rolled in, we get some better examples. Aside from being an artistic masterpiece, the Haindl Tarot court cards are informed by four of the main historical cultures on the planet: Celtic myths, Native American stories, the Hindu pantheon, and the Egyptian gods. Additionally, the trump suit of the Haindl is a beautiful mixed bag of various cultural themes punctuated with associated European astrological symbols, Norse runes, and Hebrew letters, while his pips are accented with hexagrams from the I Ching. The deck as a whole is simply stunning. Also, if we look past the Atlantean framework, the Tarot of the Ages (examples below) does some interesting cultural work in a more successful way. The Cosmic Tribe Tarot, too, a favorite of mine, (examples below) comes into being around the same time, giving an essentially Crowleyan framework a multi-racial, body positive, and sexually fluid makeover that works beautifully.

In the twenty-first century, of course, the floodgates have opened. Yet another favorite of mine from publisher Urania is the 2005 release of the Eden Tarot (originally released in German as Zukunfts Tarot, and later in French as Tarot de l’Eden) by Alika Lindbergh and Maud Kristen. This deck is a celebration of art, plants, fashion, race, culture, and tarot. From major publishers to private presses and limited editions, one can find a deck to address every little facet of our brand of primate…and any other primate…or vertebrate…or invertebrate…or gender…or proclivity, hobby, movie, or fantasy of just about any kind. The tarot market is flooded. Wonderfully as far as I’m concerned. We as potential consumers have literally thousands of options. And I think this brings me back to the veiled economic threats that caused this response in the first place: Is this really the tack we need to take with regard to tarot production? With everything going on in the world, is focusing on and berating this aspect of a spiritual and artistic practice going to define the next few years? I hope not. If an artist has decided to take the time to create almost eighty pieces of artwork, how dare someone try to tell that artist that his or her work is not worth supporting because someone somewhere on this little globe—whether overweight or gay or Muslim or disabled—might have been left out? Don’t think that representation isn’t important. This fact simply cannot be denied. Our society is better when people are free to be their authentic selves without fear of discrimination, social reprisal, or actual physical harm, but that representation will not and cannot be present one hundred percent of the time. This ideology is an unrealistic and mentally unhealthy absolutism that simply cannot be foisted onto the world at large without making the holders of this ideology miserable in its failure.

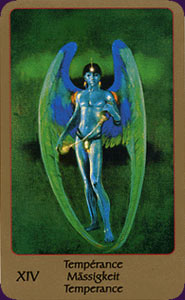

Perhaps we should instead remember this: tarot cards are pieces of paper. They have no intrinsic mystical properties. We should realize that these trumps are ideas and ideals, attitudes and platitudes. Tarots are, at their core, playing cards with a fifth trump suit added. Those trumps are likely based on Catholic, Renaissance, Neo-Platonic archetypes which refer to various steps along an organically conceived and artificially constructed journey of the soul. “Temperance” is not an angel, whether male or female, pouring between two vessels. “Temperance” is rather the Stoic ideal of moderation, found all over the world under various guises. “Justice” is not necessarily a comfortably overweight woman of color holding a scale and a sword, but rather a complex of ideals and emotions related to good conduct, social consciousness, legal authority, universal morality, and potentially crimes and their associate punishments. What I am saying is this: The tarot is not a deck of cards, the tarot is the practitioner and whatever the practitioner brings to the table. Will I continue to use the 1JJ Swiss tarot? Yes. If the deck includes a subtly anti-Semitic Devil, it is very subtle. And appropriately enough on that card, I will use that Devil to remind myself of the evils of anti-Semitism…or not, because I have no grudge against Semitic people, and therefore, I do not bring that with me to the table.

Enjoy the tarot. Use it. Meditate upon it. Reflect your thoughts inward guided by these archetypes of civilization, these representations of the Human Experience. Like all things, the cards are as useful or as much rubbish as the practitioner makes them. Enjoy the time in which we live, and save indignation for those things which are truly offensive. We are living in a time of such a tremendous flourishing of the arts and of consumerism that there must be a deck out there for any practitioner. Look around. You will find yourself in one of them, but you can find yourself in all of them.

One reply on “Can Artistic Freedom, Diversity, and Inclusion Live Happily Ever After?”

Yes, one also sees some of this insistence that decks be inclusive at indiedeckreview.com. It’s as if these folk want to gate-keep the Tarot and keep out any images that don’t fit with their idea of an ideal world and this then detracts from the card ability to show us that which we don’t want to (but sometimes need to) see.

More of the meta-Tarot stories please!

LikeLiked by 1 person