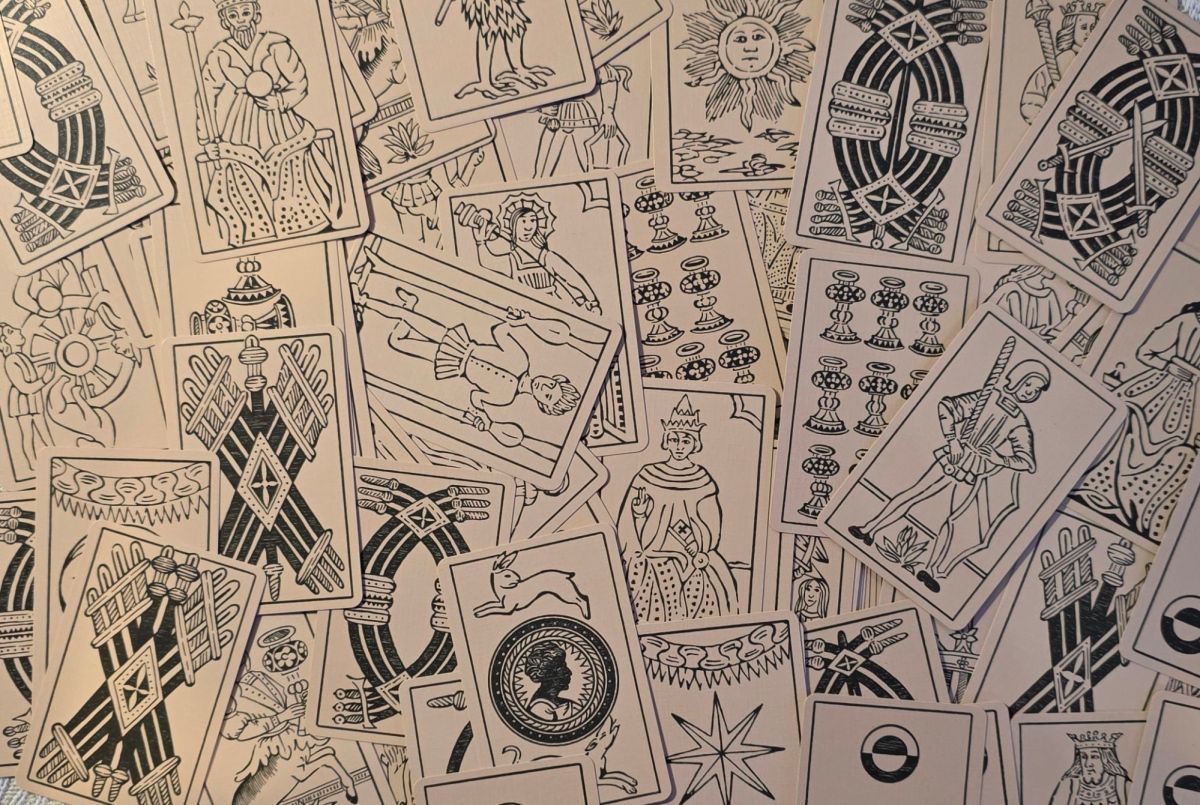

Ever since I first laid eyes on the Rosenwald images in the first volume of Stuart Kaplan’s Encyclopedia of Tarot, I have been fascinated with their primitive, elegant simplicity; for me, they are “essential tarot,” preciously uncluttered with the occult trappings of the more modern cards. Even then, however, anyone could see from the images in Kaplan’s book that the cards looked…off. As one looks a bit closer, a bit longer, the first “Aha!” escapes the lips at the realization that the Roman numerals ordering the cards are backwards…and then one notes that two of the cards have the same number. Other cards have no numbers. Odd little discrepancies are scattered here and there all over the sheet of uncut cards.

Of course, these are some of the first printed cards. And these cards appear to have been intended for the masses. They are physically small. Their images are clear, but unadorned; some might say artistically crude. They are cheap game pieces, yet even that adds to their charm. The images evoke a time and a people and important socio-cultural symbols—their archetypes, long before the term existed. The personages carved into the cards have a calm, severe warmth possibly representative of the lives of the people carving the images.

As far as firm data, there is precious little. The uncut sheets of the tarot cards were discovered in the twentieth century within the binding of a book constructed likely in Perugia, Italy, around 1501. While binding books with scrap or unusable paper was common, there is still speculation about how the tarot sheets actually ended up in Perugia. Some have speculated that the sheets may have traveled from Florence, and they do owe much stylistically to the Florentine minchiate decks of the time. Perugia was a hub of activity because as one travels from the city of Florence south to Rome, Perugia is located comfortably midway between the two. In any event, two sets of trumps were found along with two other pages of court and number cards. Three sheets—a trump sheet and two court/number sheets—are held in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., thanks to Lessing J. Rosenwald who donated the sheets in 1951.

When the sheets are seen together, several stylistic differences strike the viewer immediately, and it is quite possible that these cards were never intended to be part of one deck. Their paper quality and their size are identical, even down to the fact that they have the same number of cards on the different sheets; however, one has only to look at the trumps on the one sheet and the court and number cards on the others to realize that these three pieces of paper likely had five different sets of hands on them. Additionally, if we assume that a “traditional tarot deck” was being created, there are a minimum of five missing cards: the Queen of Batons and all the tens. (While there is technically no “Fool” card either, his absence does seem to be a deliberate choice as the “Bagattela” card appears to be an amalgam of both Fool and Street Performer.)

Even if we assume that the three sheets don’t belong together, we still have two decks that share a variety of common features: their size, their paper quality, very likely their fabrication origin, and the number of cards per sheet. Without a shred of evidence to back up my claim, I believe that what is now called the “Rosenwald Tarot” was likely a failed, transitional object: two separate deck projects produced in either Florence or Perugia by artisans trained in minchiate imagery, but trying to produce a popular “Marseille-type” deck.

A traditional minchiate has 97 cards: 40 pip cards, 16 court cards, and 41 triumph cards. If we add a fourth sheet of 24 cards to the three Rosenwald sheets in existence (assuming the two decks were somewhat similar), we end with a 96-card minchiate-type deck with the Matto/Bagattela composite eliminating the 97th odd card. However, when we look at minchiate-type decks as opposed to the Marseille-type decks, the initial trump sequences of the two types of tarots do not match. In a typical Marseille, the order of the first seven cards is usually (0) Fool, (1) Magician, (2) Popess, (3) Empress, (4) Emperor, (5) Pope, and (6) Lovers. In a minchiate, the initial seven cards are (0) Fool, (1) Magician, (2) Grand Duke, (3) Western Emperor, (4) Eastern Emperor, (5) Lovers, (6) Temperance, and (7) Strength. The trio of Duke and Emperors (or what some historical records refer to simply as the “three popes”) works well for minchiate. While these three have been interpreted in various ways, the cards we are really missing are the Popess and the Empress, but more specifically the Popess. With these exceptions, the rest of the typical Marseille trumps are found in the minchiate, which then adds these additional trumps: four elements, four additional cardinal virtues, and twelve zodiac signs. These additional trump cards are generally in the second half of the 41-card trump sequence so that the sequence still ends similarly to the Marseille pattern with Star, Moon, Sun, World, and Fame (Judgment).

To that end, I feel a sense of delicious irony that it is the enigmatic Popess that wrecks the sequence. But this is why I also feel that this “Rosenwald Tarot” might have been a failure, a victim of poor planning. Of course, the fact that the sheets were used to bind books also confirms this, but I truly wonder if this deck was ever produced as a final product. I can easily see a “new” minchiate with no separate Fool being popular with a printer who could efficiently print the deck on four 24-card blocks, but those blocks—those numbers—do not work with a Marseille arrangement. I imagine someone at a Florentine printer looking at the trump sheet pointing out the two cards of Strength and Justice and asking why the carver gave them the same number of eight and then skipped eleven altogether going from the Chariot as ten directly to the Hermit as twelve. I am sure the carver looked up and said something to the effect of “What do you expect from an illiterate thirteen-year-old?” for which he was promptly smacked.

The “Rosenwald Tarot” sheets are produced with the Marseille-type trumps, but with a solidly Florentine minchiate style in card after card. Rather than the Lover choosing between two women, he is kneeling before his beloved as Cupid watches overhead. Strength or Fortitude is shown with her column as opposed to a lion. While all the Marseille trumps are present, the order of those trumps is unfamiliar from Trump 7 through Trump 14 where the extra minchiate trumps would have been found, and the order of the final two trumps is also typical minchiate fashion: the World card comes directly before what was called “Fama” (“Fame” or simply “The Angel”) in the minchiate. This card is called “Judgment” in the Marseille pattern and comes before the World.

When we look at the other sheets, the knights are all centaurs in keeping with the minchiate practice. Also, the masculine or “long” suits of batons and swords have male valets (“fante”) while the feminine or “round” suits of cups and coins have female maids (“fantine”). As for the “two deck” theory, the Queens on the trump sheet really underscore this hypothesis. Not only are the Queens stylistically inferior to the rest of the courts, but their suit symbols also don’t match the rest of the cards of either court or pips. The Queen of Wands is missing completely; the Queen of Cups is holding a perfectly horrible blob of a cup; the Queen of Coins holds a different coin from every other coin card. As I have said, this “deck,” this “project,” may have been a failed minchiate that tried to integrate the Marseille-type trumps.

After much consideration, I have decided to take the images and create a tarot deck based on the “Rosenwald images.” This is certainly not a new idea. Only to name a few of my favorites, the Rosenwald Tarots by Marco Benedetti (search his name on FaceBook), Sullivan Hismans, and Krisztina Kondor are well known in the tarot community. Their decks display remarkable craftsmanship and a dedication to the spirit of the original deck. I, however, have no interest in producing a facsimile of a 500-year-old deck that feels 500-hundred years old.

My goals with this deck are expressed in the title itself, the “Rosenwald Redux Tarot,” the Rosenwald images brought back, resurgent. Certain artistic liberties were taken, of course, but I have tried to preserve the simplicity and uncluttered charm of the original. To avoid some confusion, I will make clear what changes I have made to these images that I personally revere so much. The first notable quality will be the size of the cards themselves. The original Rosenwald cards measure two inches by three and a half inches; the Rosenwald Redux Tarot is drawn to accommodate a standard “bridge-size” card, which measures 2.25 by 3.5 inches. When comparing the original to the Redux, one will note the images are oriented slightly differently to integrate the quarter inch of difference in their widths.

The second most obvious difference between the sheets kept in the National Gallery and the Redux is that I have reversed the first sheet of images. While certain cards appear directionally odd when compared to other traditional decks (for example, the Hermit faces the “wrong” direction), the main arguments for the reversal are (1) a backward-seeming order on the sheet, (2) the reversed Roman numerals on so many of the cards, and most damningly (3) a trump sheet at a German museum which is identical to the National Gallery trump sheet except printed the correct way. Given the wealth of evidence, reversing the images seemed only logical.

Additionally, I removed all the Roman numerals. Not to sound like the snob that I am, but I assumed that because of the historical nature of the deck, many of the people who would be interested in having this deck would already be familiar with tarot. Historically, various tarots have had some interesting orders of the trumps, and the Rosenwald sheet is no exception. I have also consolidated what appear to be the stylized points of a trefoil arch in the corners of many images of the trump sequence; however, taking an artistic cue from the original carvers, if the card’s image was not able to artistically manage the corner points, those points were eliminated as is the case with many of the higher valued trumps of the original sequence whose images became fuller and more visually complex.

As to the incompleteness of the Rosenwald Sheets, I have created quite a few extra cards. The first candidates were, of course, the Queen of Batons and the four tens of the pip cards. The Queen of Batons is a composite of various attributes of the other three queens with a few details to give her a little personality. The tens were oddly taxing as there are several examples of how the number ten was handled in various extent cards from the period. I decided to follow a more direct Marseille-style on the Batons, Swords, and Cups, while executing a straightforward Visconti-Sforza style for the Coins. In the interest of making the deck a bit more useful to the modern cartomancer, I also created a separate Fool card to complete a traditional Marseille-style trump sequence.

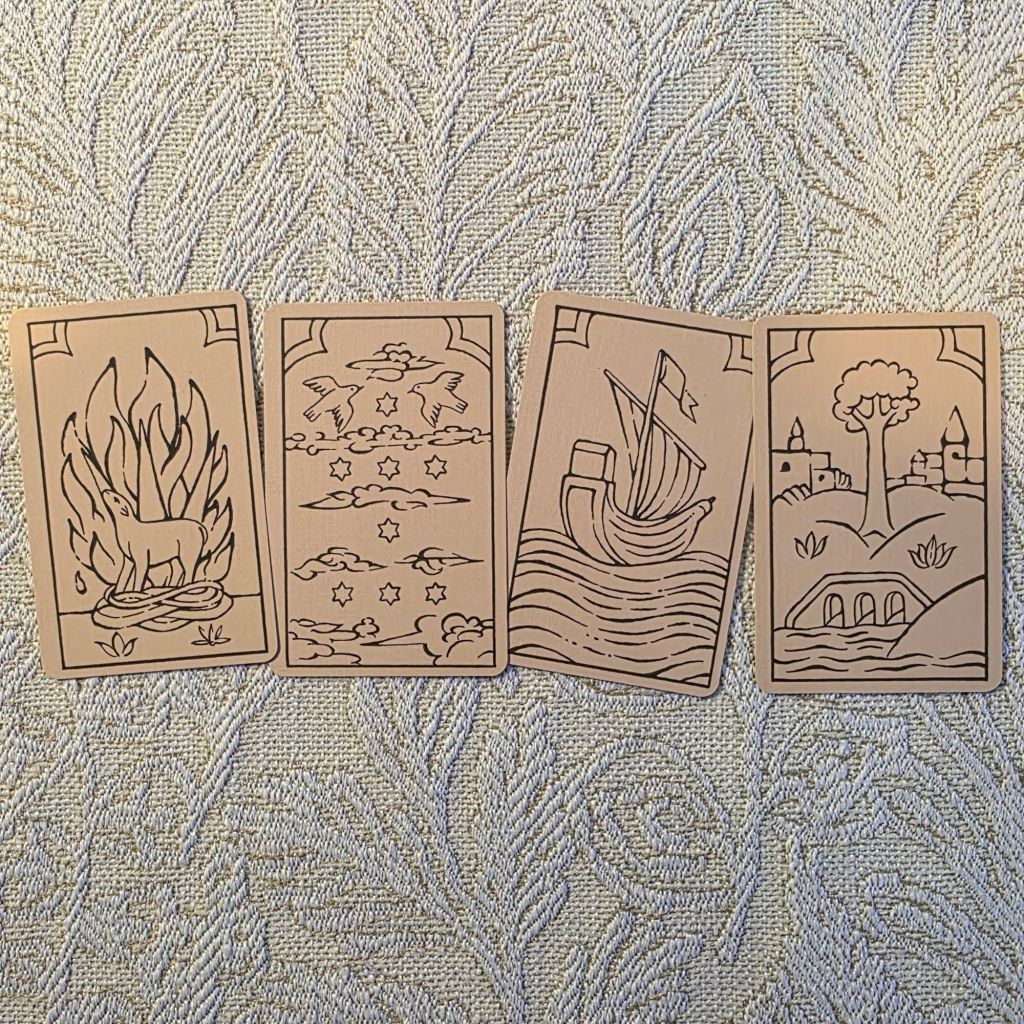

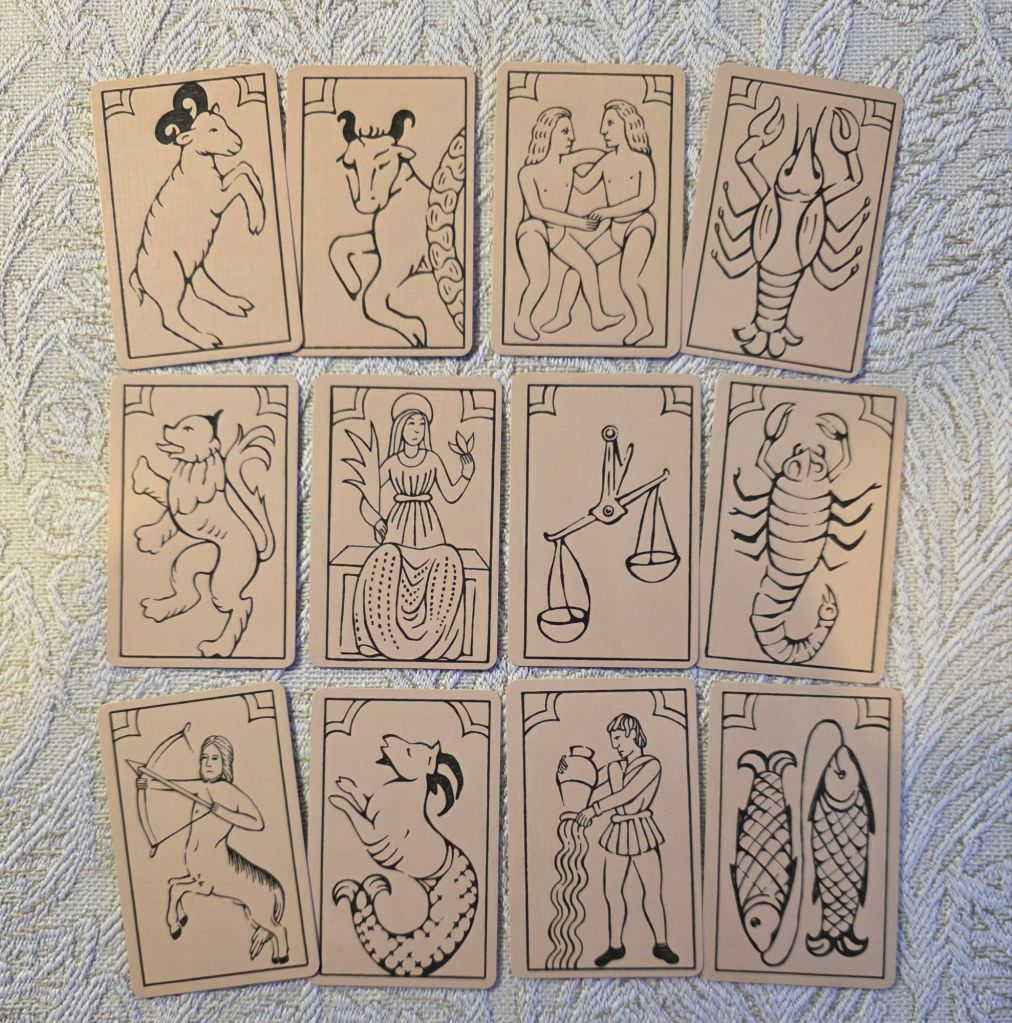

Next, as I continue to view the sheets as perhaps an odd minchiate misstep, I have decided to complete the minchiate trumps after a fashion. The Rosenwald Redux Tarot is a 98-card deck, a theoretical minchiate as it were, as I have added the additional four cardinal virtues, the four elements, and the twelve zodiac signs. To the best of my ability, I have researched various contemporary iterations of these images as well as experimenting with how those images would translate into a style similar to the Rosenwald sheet. The additional cards are, I hope, as simple, straightforward, unadorned, and charming as their original Rosenwald inspiration.

I hope that this explains what I have been doing and why. This project has been a delight, and I hope that there are some of you who will continue this journey with me. The photographs included in this post include pictures of my prototype (and special thanks to Jeremy, whose technical graphics expertise saved me so much heartache), but my final goal is to have about 500 decks printed for sale through crowdfunding. The deck will be made with a black-core, 310-gsm, linen finish cardstock so that they will be strong and light and shuffle beautifully. At this time, to keep publishing costs down, I have decided on a tuck box, with a two part cardboard box as a possible upgrade should funding permit. Publishing goals aside, this project has given me such feelings of both purpose and peace that I would do it all over again whether I sold one or not. I hope you enjoy the “Rosenwald Redux Tarot.”

(The Kickstarter Campaign successfully funded in December 2025, so I removed the link, but left the picture.)