I am a total sucker for a list of just about anything. List of top ten best episodes of Star Trek? Reading it. List of ten worst episodes of Star Trek? I’m there. A list of the books some YouTuber read this year? Watching. Video of Top Ten Rider-Waite-Smith decks currently in production? One of the “views” is mine. An entire book devoted to a list of authors that Harold Bloom considers The Western Canon? Guilty. And I like these lists because I have practically never discovered anything of value on my own. I have never been the person to say, “Oh—I read/watched/found this great new whatever…”

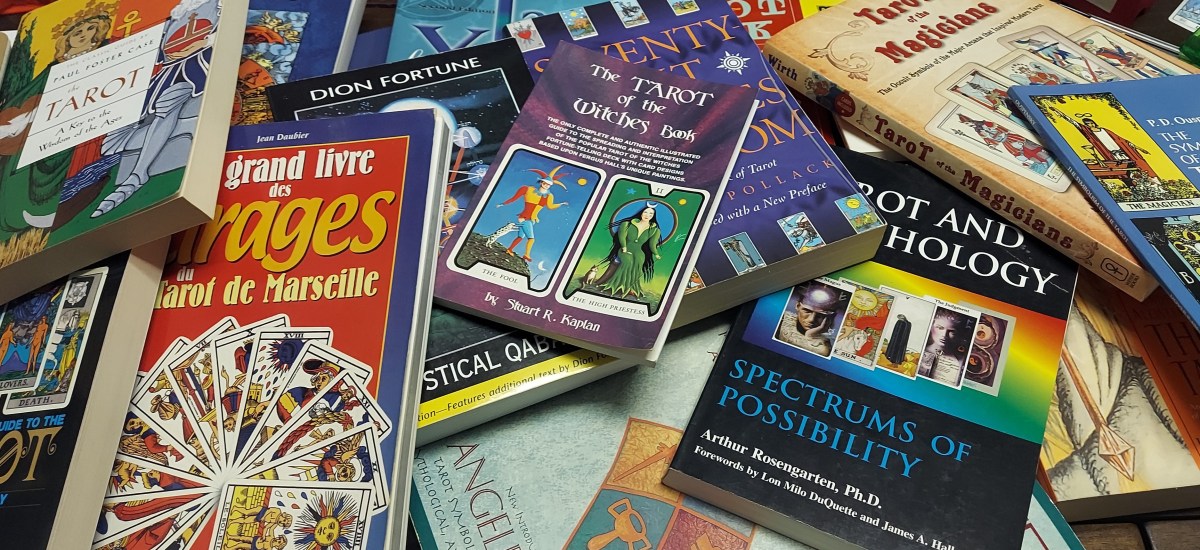

When it comes to tarot, however, I am well read. Now that I think about it, when I started reading books about the tarot some thirty or so years ago, I probably did stumble across some new reads on my own because the technology and resources that we have today didn’t exist. We had the occasional chain bookstore and mail-order. Some of those good old books were absolutely foundational to my studies of the tarot, and I reach for them to this day. While compiling this list, I noted that these are the books which create the most complete picture of not only what tarot means to me, but also how and why I use the cards as I do. Also, while no conscious effort was made to neglect more recent contributions to the corpus of tarot literature, I did notice that the newest of these books is now twenty-four years old, probably older than some of you reading this right now. I am reminded of the truth in Napoleon Bonaparte’s axiom: “To understand the man you have to know what was happening in the world when he was twenty.” Without further delay and in no particular order, my top five most used books on the tarot are:

1) The Book of Thoth by Aleister Crowley (US Games Systems, 1995). As I have mentioned in other posts, Crowley’s Book of Thoth is the first book that I ever read on the Tarot. Having been exposed to older literature as a youth and having grown up around various sets of old Southern grandparents, his tone of arrogant and elegant Victorian authoritarianism was not as off-putting to me as others have no doubt found it. Having come back to his essays time and again, I more easily overlook his confident, perhaps supercilious air and can appreciate his actual intelligence. For all his bluster and pomp, the man was a genius-level master of synthesis; his efforts—aided tremendously by the prior trials and errors of the various magickal orders into which he was initiated—to create a tarot-based unity of the world’s major religions, past and present, with their various symbols, numerological significances, and even languages, must be respected. He borrows ideas and concepts from everyone and everything from Zoroaster to the Egyptian Book of the Dead to the Greeks to the Periodic Table of the Elements to the “Yî King” (I Ching) and everything in between…and all attached to a Hermetic Qabalistic framework. It’s quite impressive.

One aspect of his thought process about the tarot that fascinates me more and more as I grow in this path is what I hold to be his sincere belief that the cards are “living beings” (46). This leads directly to a facet of the work that I believe some people miss: Crowley spends very little of his book on “divinatory meanings,” but rather he writes concise descriptions of the emotional and social states that the cards should evoke as a combination of “environmental factors” like elemental, numerological, Qabalistic, and zodiacal dignities. He writes about the cards as if he is truly getting to know them. His descriptions of the Court Cards remain nonpareil with their insightful and empathetic descriptions of real people. All in all, Crowley’s ultimate faith in the unifying and universal nature of the tarot continues to inspire seekers to this day.

2) The Complete Guide to the Tarot by Eden Gray (Bantam Books, 1972). A perennial classic that perhaps doesn’t get the love it should, Eden Gray’s Complete Guide to the Tarot was the bookstore chain favorite of my youth. I had my second copy for a couple of decades and had even colored many of its “lavishly illustrated” pages (It has almost full-size black and white line art of the Rider-Waite-Smith on the page facing the definitions.) “Misplacing it” (and yes, I do blame my children…) was heartbreaking to me, and another copy took its place—on my shelf, if not in my heart—as quickly as I could get it. The classic Bantam paperback hasn’t changed in at least three decades except that the price is now around eight or nine dollars as opposed to the buck-ninety-five I paid originally.

When I was contemplating this list, I thought about the fact that Bantam had not issued a fancy “50th Anniversary Edition.” First published in 1970 and acquiring its final form in ’72, Eden Gray’s modern tarot classic deserved some hoopla. My indignation demanded it, and Bantam insulted me by not providing something that they had no idea I wanted and that they had no interest in producing. My bruised feelings, however, soon gave way to those nostalgic warm fuzzies, and I realized that an overproduced version of this precious, inexpensive, unchanging, utilitarian vade mecum would defeat the entire purpose of its existence. Though Bantam could update the line quality of its images, it is perfect as it is.

Within the book itself, Gray sprints through the history of the cards, introducing the reader to some of its legends, facts, and occult adoption. For a book labeled “Mysticism and Occult” by the publisher, she does skirt some deeper treatment of those occult influences in favor of getting to the cards. Of those card definitions, some detractors would say that Gray has created something little better than the ubiquitous Little White Book; however, I think it bears mentioning that at the time of the book’s original printing, those LWBs were not nearly as commonplace as they are now. After the definitions of the cards, Gray introduces a few spreads including the “Keltic Cross” layout I originally learned. She then goes further into more solidly occult matters with a very pleasing introduction to Golden Dawn-based astrological links and Qabalistic associations where she strangely almost never mentions the Golden Dawn itself. But more on that later…

3) Tarot Plain and Simple by Anthony Louis (1st edition, Llewellyn, 1997). If Gray’s little tome is our pocket dictionary to the tarot, then Anthony Louis’s Tarot Plain and Simple is our thesaurus. He creates a beautifully structured book that is a readable, yet thorough look at the cards. While he admittedly eschews the more formal and pedantic systems for learning the tarot, his descriptions feel complete and engaging. Louis presents a brief history of the cards along with some classic spreads that he methodically examines and very organically explicates. When we arrive at the cards themselves, he begins with a straightforward word or two of definition, but it is his lengthy and many-directional, rapid-fire “Key Words and Phrases” that do this old logophile’s heart good. A “Situation and Advice” section adds context to his lovely panoply of synonyms, and he ends with references to types of people that the cards may refer to in lieu of or in connection with the definitions.

The title doesn’t do justice to the care and concern with which Louis obviously chose his words. After reading his sections on tarot journaling and note keeping and noting his here-and-there allusions to various pop culture and literary canons, reading his definitions feels as though we are perusing the author’s own tarot commonplace book. The book ends with some tables that briefly look at the various astrological and numerological systems associated with the cards. This book provides a thorough overview of the cards themselves with enough information to help a practitioner of any level. I know that this book is in its second edition, at least, but I have been using my first edition from 1997 since that year. If there are many changes in the new edition, I don’t know what they are, but I do hope that he has updated—read “removed”—his sample reading on the failed presidential campaign of businessman and odd political footnote Ross Perot.

4) Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom by Rachel Pollack (Red Wheel/Weiser, Revised 2007 edition). This book helps me to understand better that tarot may work simply because humans are very predictable primates, and in a projective sense, seventy-eight cards (and possible reversals to double that number) really do outline the majority of things that the average human can experience. Don’t misunderstand: the book is exquisite and my copy, in particular, has pathways in it that are worn with the traffic of so many eye tracks. When I talk about predictability, however—almost a pun about a book on a divinatory tool—I mean that I love the book for the same reason that Rachel Pollack wrote it as she did: at some point in our lives, we—Pollack and myself—have both been liberally-educated English teachers. Certainly Pollack’s résumé is filled with books and writings that have nothing to do with tarot, but the essays and meditations that fill Seventy-Eight Degrees were written by a scholar who was educated in the late sixties or early seventies in the now-flagging Elysium of the Liberal Arts when the canon was still respected even as a series of new socio-cultural perspectives and theories were being introduced to broaden the interpretation and scope of the literature.

To you, dear reader, all that pseudo-academic gobbledy-gook means this: the wealth of literary, historical, mythological, cultural, and psychological allusions with which Pollack infuses this book are accurate and comfortable. She brings a depth of understanding not only of tarot specifically, but also of humanity as a whole. In the essay on the Fool, Pollack introduces one of many bits of wisdom in the book when she discusses the fact that the Trickster character appears far more often in uncodified mythologies rather than institutionalized churches because mythologies explain our fears while institutional religion offers us a spiritual safety net. Her language is clear and readable, yet with a respectful and scholarly bent. She writes as though she and reader are having a lovely and intelligent conversation about life that also happens to relate to the tarot.

5) The Qabalistic Tarot by Robert Wang (Marcus Aurelius Press, Revised 2004 edition). As often as possible,I try to avoid the trap of labeling the contents of a book based on who “should” read a book. I am not going to tell a fourth grader that he or she should not read Moby Dick; however, realistically, a fourth grader might get less out of Moby Dick than an older reader, one with broader life experience or more familiarity with the time period or with Melville’s expansive vocabulary and challenging syntax. Having said all that, the first time I read The Qabalistic Tarot, I felt like a fourth grader reading Moby Dick.

Robert Wang is an exquisite writer who has managed to clarify as much as is possible the extraordinary relationships that exist between the Hermetic Qabalah and the tarot. Over the last decade, I have read this book aloud from cover to cover about every other year. And every time, I am newly impressed by the enormous amount of scholarship and respect that Wang conveys when discussing this very questionable subject of projecting a card-game divinatory practice onto an arboreal mnemonic tool created for ascending the mystical heights of the Jewish faith. But the book works, and I adore it.

Of all the tarot literature I had read to that point, I had never been given the most fundamental, systematic underpinnings of why the cards mean what they do. Using illustrations from his own Golden Dawn Tarot (US Games), Crowley’s Thoth Tarot, the Rider-Waite-Smith, and the Tarot de Marseille, he establishes the ground rules of the sephirot and the various astrological and Hebrew associations, but then he approaches the tarot in what I still find the most revolutionary (and logical) way: from the bottom up. Based essentially on the teachings of the Golden Dawn, Wang constructs the tarot deck backwards, beginning with the tens of the suits, which inhabit the tenth sephira Malkuth, the Foundation. From that most relatable, concrete starting point, Wang works his way up the Tree of Life through each of the ten sephirot until we get to the most nebulous and potent Aces inhabiting the Crown Kether. We then begin again at the bottom with The World trump, located on the path connecting Malkuth to Yesod, the two lowest sephirot. Again, we work up the Tree of Life using the pathways joining two sephirot until we reach the top, the essence of mystical wisdom and knowledge of godhead, the Fool. Again, I am still stunned and overjoyed at how useful this type of deck construction is for learning the tarot.

Wang’s “textbook of mystical philosophy” makes more sense every time I read it because I read other things in between like the other books on this list, The Tarot: A Key to the Wisdom of the Ages by Paul Foster Case, The Mystical Qabalah by Dion Fortune, Understanding Aleister Crowley’s Thoth Tarot by Lon Milo DuQuette, and the list goes on and on. In fact, I have discovered over the years that one of my favorite practices is to read Wang’s Qabalistic Tarot and Gray’s Complete Guide to the Tarot simultaneously. At first glance, Gray’s antique little paperback is so unassuming that one might never guess that she actually bases her card meanings less on Waite than on the Golden Dawn writings. When it comes to a nice summary or divinatory keywords to wrap up a page or five in Wang’s more ambitious work, Gray is a satisfying cap to Wang’s longer prose.

So while I would never discourage anyone from reading The Qabalistic Tarot, I would tell the potential reader that this book is not an introductory look at tarot card fortune telling; Wang gifts his reader with a masterfully written, holistic approach to explaining the Hermetic Qabalistic approach to the tarot that has developed over the last few centuries, and if the reader is serious about the tarot as a part of his or her spiritual practice, this book may well be revisited time and again.

Having never really thought about it, I now find that these five books really do form the cornerstone of what tarot means to me and how I use tarot in my life. They have been an unceasing source of information, comfort, and growth to me over these last couple of decades because, like all good books, they have changed and grown as I have changed and grown, and they are rejuvenated every time I read them with eyes made new by the accumulation of experience and learning.

One reply on “My Top Five Tarot Books of All Time”

[…] My Top Five Tarot Books of All Time — The Tarot King of Mississippi […]

LikeLike